Over the course of our time in the United Kingdom, primarily the city of London, England, we were given the opportunity to explore the history of European cinema through various tours and excursions to a number of locations that served as places of inspiration and/or production in the world of film. From walking through the streets of London to visit locations that took place in the James Bond films, to visiting Warner Bro.’s studios where much of the Harry Potter franchise was filmed, and even attending a few showings such as the one for the film Britannia Hospital. Even from my personal excursion outside of London to visit the city of Bath and small village of Lacock, I was able to gain some insight on the films that had been filmed in these locations as well (e.g., Les Misérables, the Harry Potter franchise). Overall, for the first leg of the trip in this particular course, it was quite interesting to see just how much history with regards to European cinema existed here in the UK alone. I will be speaking on about a few experiences in particular that served to be rather intriguing to me as my time spent in London progressed, starting with the Hitchcock walking tour.

Alfred Hitchcock Walking Tour

Before taking this class, I had previously taken an auteur-focused course on Alfred Hitchcock at my university back in El Paso, Texas where we covered a number of his films that, interestingly (or rather unsurprisingly) enough, were also mentioned during our Hitchcock walking tour as well as a few details regarding many of his films generally speaking. I recognized a few of the locations that were used in his 1972 film, Frenzy, including the building where the killer had lived and committed another one of his murders. Seeing these locations in person was quite surreal and was a feeling that I never quite got over as the days went on as I continued to picture how it must have looked all those years before when a production crew, along with Hitchcock himself, were filming here. Furthermore, the guide also gave us some information that I also remembered covering in my previous course regarding one of my favorite films of Hitchcock’s, Rope, where he expressed how the film was meant to present the illusion of being one continuous take. Furthermore, The guide went into a bit of detail regarding how Hitchcock became a master of his craft from his early involvement with what would down-the-line become Paramount studios, to his assistance with various directors in his early involvement with the film industry, to eventually directing his own works such as The Lodger, of which is considered to be his first ‘Hitchcockian’ film for its suspense/thriller nature (Brill, 1983). I will say that one piece of information that I was quite surprised to find out, considering that Hitchcock is well known to have been the ‘master of suspense’ as a director was the fact that he had apparently directed a musical. Considering that much of Hitchcock’s auteurship, which as Truffaut expresses is essentially the way in which a director uses the medium of film to depict their own unique artistic expression within their cinematic productions (Truffaut, 1954), is largely based on his methods of depicting/generating suspense and creating films covering darker or more serious themes of death and psychological duality I found it quite surprising to find out that Hitchcock had directed a musical romance film called Waltzes from Vienna.

Harry Potter Film Locations and Warner Bros. Studios

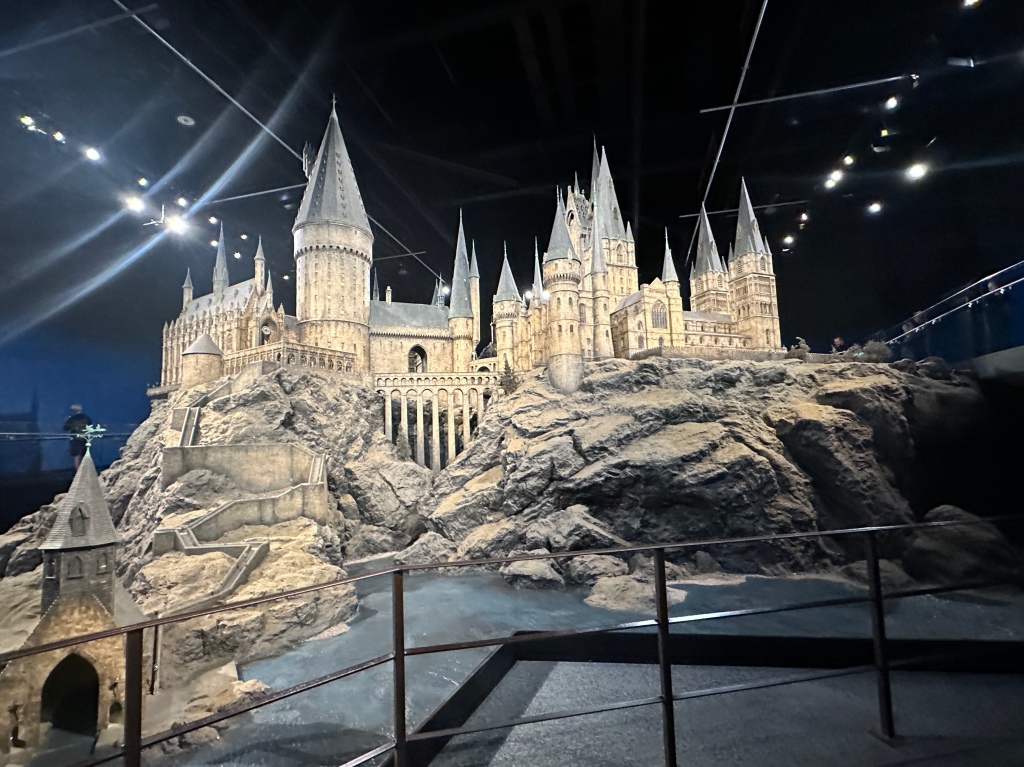

That surreal feeling of being in the same place that once held a film crew and all that came with it was only strengthened ten-fold by my various excursions to locations with ties to arguably one of the most popular film franchises of the 21st century, Harry Potter. These were the films that I was provided an abundance of information on with regard to various aspects of their production, largely involving set, costume and character design. Outside of class through these instances it was quite interesting to see how the franchise made use of the British iconography that we had spoken about for further promotional purposes of the films themselves or even the country in which they were based in to a much larger transnational audience as the franchise grew in popularity. While traversing around London I had noticed a number of stores that were ‘Harry Potter’ themed and consisted of an abundance of merchandise related to the series. From clothing displaying the individual Hogwarts houses to small collectibles referencing Platform 9 ¾. When visiting Warner Bros. Studios in London this became incredibly more apparent as I made my way through the tour and shops. The shops consisted of various sections pertaining to variations of their merchandise, with a surplus of it consisting of the Hogwarts houses to further idealize the image of a traditional English boarding school (much of it, I noticed, being the merchandise also sold at other locations such as Universal Studios in Los Angeles).This idealization of the English boarding school is something that is even further achieved through much of the tour itself, where people are presented the opportunity to essentially ‘jump into’ the wizarding world of Harry Potter by viewing a number of the places in Hogwarts by traversing around and even through some of their finished sets (e.g., the Gryffindor common room, Snape’s potions classroom, the dining hall).

Warner Bros. Studios.

A few other things that I noticed were, again, in relation to popular forms of British transport such as the train, with a whole section of the tour being dedicated to displaying the train from Platform 9 ¾ where fans could either purchase a small amount of exclusive 9 ¾ merchandise, go into the train itself, or even take costly pictures while sitting on the seats as a green-screen played in the background to give the illusion of being on a moving train similar to the characters in the films. With further regard to the promotion of British public transport, they also appeared to promote the iconic double-decker bus through the representation of the larger, purple ‘knight bus’ in some merchandise as well as displaying the bus itself for fans to go on and take pictures with. Overall, through physical representation of the sets and items used in the filming process, as well as presenting a section dedicated to concept design for the franchise in order to further emphasize the sheer attention given to building such a tangible world combined with aspects of already existing British culture, I feel that the franchise has succeeded in promoting to their transnational audience on such a scale that it has even left an impact on travel into the United Kingdom.

In one of the articles that I had briefly touched upon for my first quiz, it spoke about how the franchise had also appeared to developed what the writer considered to be a form of ‘screen tourism’ in which fans of the films largely travelled to the UK to visit real locations with a basis in fiction (Cateridge, 2015). Not only has the franchise generated this sort of ideal perception of a number of existing aspects of British culture, but through this, it has also generated travel largely based upon this idealization. Cateridge mentions how while they were in Oxford they had noticed groups of people visiting locations that had taken place in the films, where they could take pictures of themselves “apparently in Hogwarts” (Cateridge, 2015). He described it as this sort of “imaginary map of ‘Oxford’” which ties into the growing concept of ‘screen tourism’ in which people journey around to areas based off of a particular fictional ‘movie map’ that has been developed and inspired by the associated film production(s) with it. It was in Lacock where I was first given the briefest glimpse into this type of ‘movie map,’ where I got to see the exterior of the Potter household that was in Godrick’s Hollow. In Oxford, we had the opportunity to walk through a narrow passageway that may have inspired Diagon Alley, as well as stand outside the building where a number of scenes in the Hogwarts courtyard had taken place. Overall, to see how much this franchise has had an impact on its audience either through the representation of their displayed purchased merchandise on themselves or even their potential means of travel to the UK, I find it quite interesting to have been able to see just how much this franchise has served to display various aspects of British culture to a larger transnational audience (including myself).

References:

Cateridge, J. (2015). Deep Mapping and Screen Tourism: The Oxford of Harry Potter and Inspector Morse. Humanities, 4(3), 320-333.

Brill, L. W. (1983). Hitchcock’s” The Lodger”. Literature/Film Quarterly, 11(4), 257-265.

Truffaut, F. (1954). A certain tendency of the French cinema.

Journal 2: French New Wave to the J. Cameron and S. Coppola lenses of Cinema

After leaving the United Kingdom by train, we made our way across the water to the next major stop on our journey to continue to explore the various aspects of European Cinema, France. During our class lectures we covered the movement of the French New Wave of cinema, which essentially referred to films that largely presented an objective focus of the world through the lens of auteurs often through unconventional means of filmmaking that deviated from typical cinematic production which would serve to further characterize the film as a personal piece of artistic expression rather than a generic work (Neupert, 2007). Considering the fact that we had already briefly touched upon the concept of auteurism with Alfred Hitchcock back in the United Kingdom, I found it to be quite interesting how it could also potentially be applied to a few of the other directors that we took the time to look at during our stay in France, such as James Cameron and Sophia Coppola.

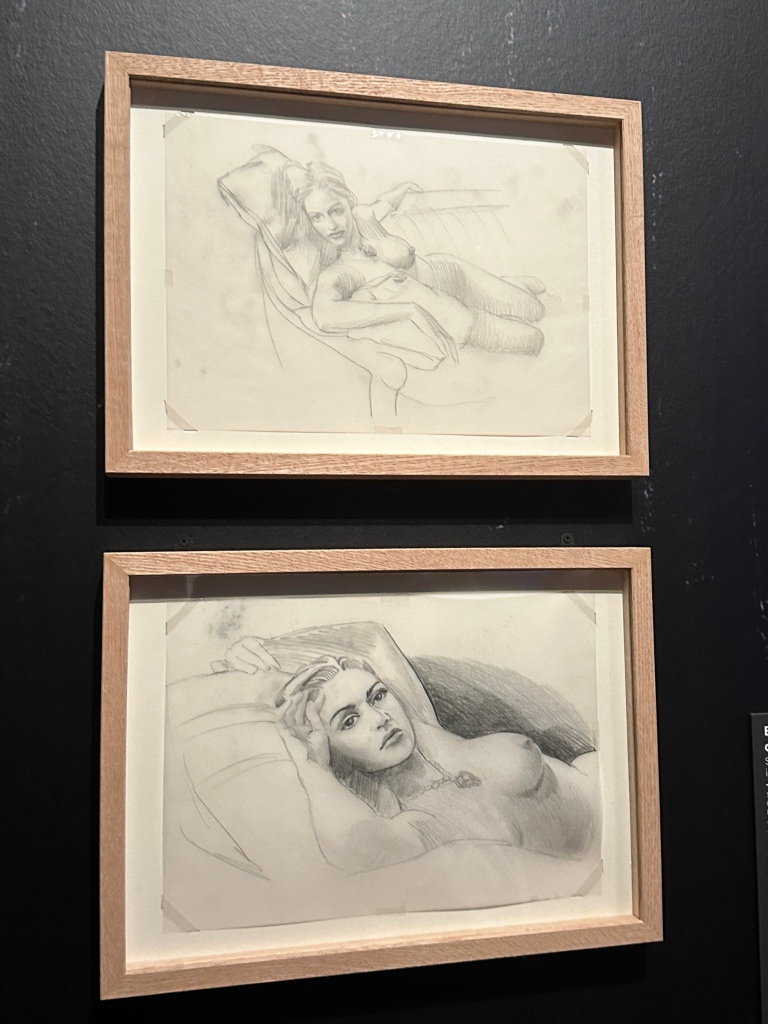

The James Cameron Exhibition

Before going into the exhibition, I have to say that I genuinely had no idea that James Cameron was a legitimate artist in terms of drawing. As an artist in this regard myself, I was absolutely astonished at sheer amount of drawings he had produced since such a young age, and even furthermore with just how skilled he was at putting his concepts to paper. As Tasker expresses in their writing regarding Cameron, he is often known for delving into the realm of science fiction (e.g., Avatar (2009), Aliens (1986), The Terminator (1984)) which is where I feel his artistic abilities truly shine through the concept design he makes in an attempt to bring such unearthly visuals to life within many of his works (Tasker, 2002). It was then that I also began to take notice of just how much of Cameron’s work not only presented a focus on science fiction-based settings, but also that many expressed Cameron’s personal interest in the ocean and his desire to explore its expanses from the wreckage of the Titanic (Titanic 1997) to the depths of the trenches below us (The Abyss 1989). Another significant feature of his work that was pointed out to us by our guide throughout the exhibition was Cameron’s focus upon the intricate depiction of the eye as a form of intense internal expression in his characters, which is something that can be seen in his early works of art up to movies such as Titanic and the Avatar films. Based off of going through this exhibition, I feel that Cameron has a keen eye for developing his personalized vision of other-worldly landscapes and his characters in relation to such imagined landscapes often through his own drawings and conceptual designs.

Sophia Coppola’s Marie in Versailles

In contrast to Cameron however, Sophia Coppola takes a different approach to the types of landscapes and characters that she portrays in her work, which often take a much more down-to-earth perception of the existing world. S. Coppola often depicts her settings in real locations rather than recreated sets, which can evidently be seen in her film Marie Antoinette (2006) where the Palace of Versailles is depicted as the main setting for the film. As I visited the palace during my stay in France, it was nice to see just how much of the true nature of the large palace was kept the same within the depictions of it shown in Coppola’s film. Furthermore, another key characteristic of her work, as expressed by Kennedy in their article, is that she primarily attempts to comment upon female subjectivity and “post-feminist concerns” regarding consumption as a “feminine ideal” (Kennedy, 2010). This is something that can be seen through the way in which Coppola portrays the character of Marie in relation to her surrounding environment; small and centralized in a sea of onlookers and constant observers. In other words, the objectivity of Marie as a female is tangible. While at the Palace of Versailles, I could feel this claustrophobic sense of objectiveness whenever I looked at the palace itself and all that it held which was often surrounded by visitors like myself observing from all possible angles at all points throughout the day, which is shown by the fact that many of the pictures that I took while there were hardly ever absent of people.

References:

Kennedy, T. (2010). Off with Hollywood’s head: Sofia Coppola as feminine auteur. Film Criticism, 35(1), 37-59.

Neupert, R. (2007). A history of the French new wave cinema.

Tasker, Y. (2002). James Cameron. ROUTLEDGE KEY GUIDES, 81.

Journal 3: The Breathing and Bustling City of Italian Neorealism

A Realistic Depiction of Rome

When we made our way over to our last major stop to explore European cinema, Rome, Italy, we decided to cover a particular film movement in class known as Italian Neorealism. This movement largely referred to films that seemed to have some amount of desire to express realistic stories of the poor and working classes in unconventional manners of filmmaking that often conveyed a documentary-like feel to their depictions (Lawton, 1979). As Shiel phrases it, this mode of filmmaking was meant to express the “ontological truth of the physical” with regard to the happenings of said classes and the environment itself (Shiel, 2006). As I watched clips from significant films from this movement such as Bicycle Thieves (1948) it was clear to see how they translated the natural experience of our surrounding environment into the cinematic format. What I mean by this is that the “naturalistic tendencies” that Perry speaks about in their writing with regard to Italian Neorealism are heavily displayed through the camera to depict the environment in the most realistic and natural manner without the aid of controlled aspects of lighting and other technical means of production (Perry, 1979). The characters blend into the bustling environment of the living Rome depicted on the screen in Bicycle Thieves, where the viewer can easily lose sight of them. I found this to be quite similar to my experience traversing the city of Rome in real life. Even to locations that seemed to display a more central focus on the characters as in Roman Holiday (1953) or the fountain scene in La Dolce Vita (1960) in the cinematic format, it was intriguing to see how true to life Italian Neorealists depicted the every lively environment of Rome that truly exists beyond the traditional cinematic depictions of classical film.

References:

Lawton, B. (1979). Italian Neorealism: A Mirror Construction of Reality. Film Criticism, 3(2),

8–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44018624

Perry, T. (1979). Roots of Neorealism. Film Criticism, 3(2), 3-7.

Shiel, M. (2006). Italian neorealism: Rebuilding the cinematic city. Columbia University Press.